Connect one-on-one with a legal expert who will answer your question

Speak With An Employment Lawyer

Connect one-on-one with a legal expert who will answer your question

The Coronavirus pandemic continues to cause confusion and anxiety as an estimated three out of four Americans are or will be under orders to stay-at-home until April 30, 2020. For those members of the public who are still working in essential jobs like healthcare and food-service, a large part of that confusion and anxiety revolves around their rights to a safe work environment and employers’ obligations to provide that safe environment.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified Coronavirus as a pandemic. The WHO is an international agency organized under the United Nations that sets international health standards and provides guidelines on health issues. A pandemic is a widespread occurrence of an infectious disease that crosses international boundaries. The WHO’s classification of a pandemic is important because it signaled to world governments the severity of the virus and that they needed to take the Coronavirus more seriously.

The Center for Disease Control (CDC), the main federal agency in the United States tasked broadly with protecting the nation’s health, recognized the WHO’s classification of the Coronavirus as a pandemic shortly thereafter. The CDC’s treatment of Coronavirus as a pandemic is important because although the word might not carry a legal significance, the determination means that the virus spreads easily worldwide and is not currently contained. The classification of any virus as a pandemic legitimizes employees’ concerns over workplace safety and should encourage employers to take additional measures to keep workplaces as healthy as possible.

Although many states, including California, New York, and New Jersey, issued orders requiring all non-essential businesses to stop operating, both essential and non-essential employers continue to operate. Those businesses still operating must be mindful of the variety of federal and state regulations that require safe workplaces. The management of a worldwide pandemic is complicated for obvious reasons and implicates a variety of federal and state regulations carried out by different agencies. This article explores some of the workplace safety obligations and compliance issues facing employers during the pandemic and the interplay of some of those federal and state regulations as applied to the Coronavirus.

Employer Workplace Safety Obligations

Employers have a legal duty to provide a safe work environment to all employees. All private sector employers must comply with the regulations created by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Congress passed The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 to implement regulations to protect workers from being killed or harmed at work. OSHA’s regulations can be found in 29 U.S.C. section 651 et seq. and 29 C.F.R. section 1902 et seq. and cover basic workplace safety requirements, as well as specific industry regulations.

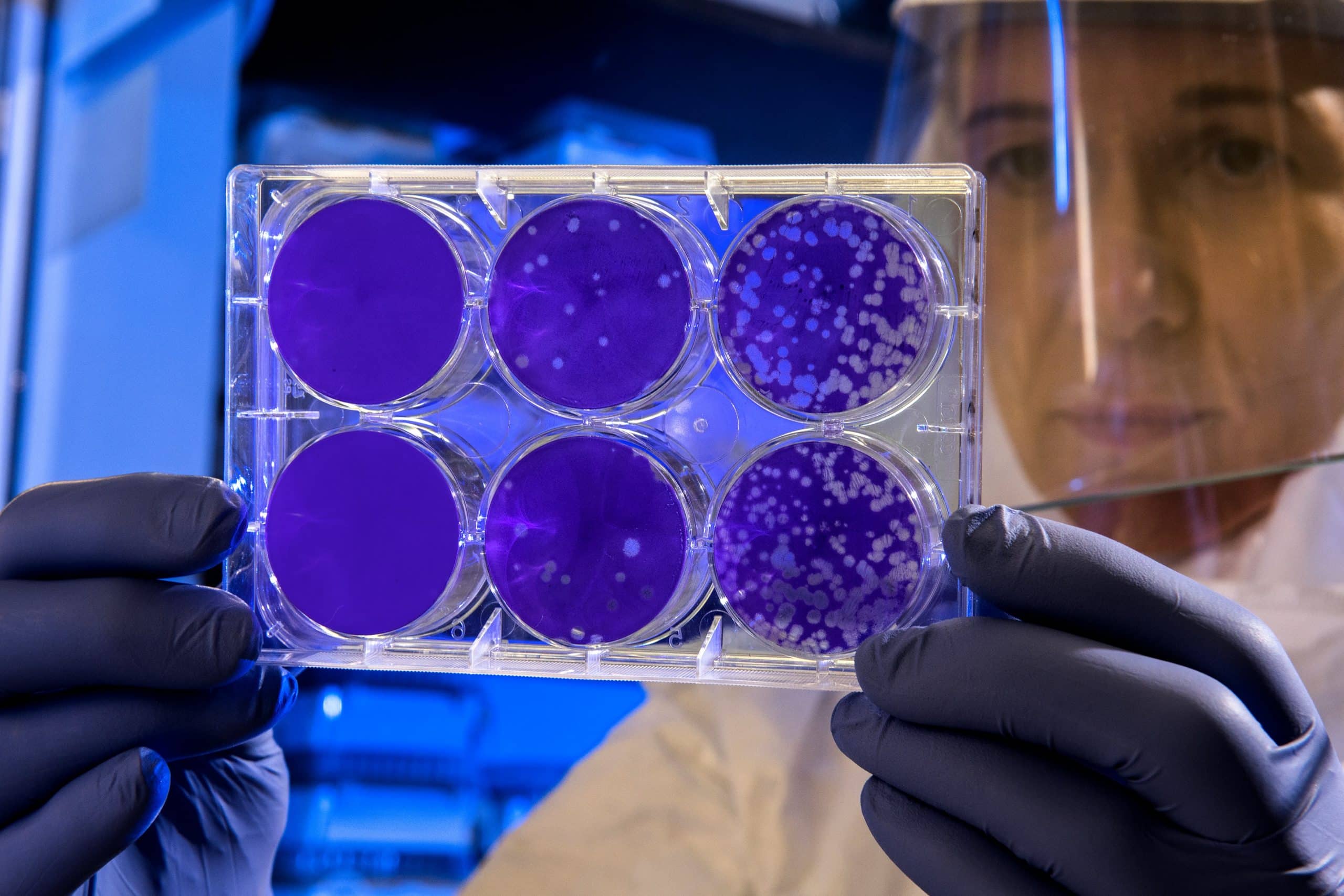

OSHA regulations are particularly relevant during the Coronavirus because employers who continue to operate are potentially exposing their employees to known, unsafe conditions. Workplace safety concerns and allegations of widespread lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), like masks and gloves, have prompted foodservice employees at Instacart to strike this week of March 29,2020. OSHA recommends that workers who are at high risk to exposure need to wear gloves, a gown, a face shield or goggles, and either a mask or respirator, depending on their jobs. Employers should carefully consider employees’ requests for PPE and provide necessary PPE when possible.

On top of these federal OSHA regulations, most states have additional state-operated workplace safety programs. Employers should consult their state’s OSHA website for additional guidance on Coronavirus.

To assist in providing a safe workplace, employers can also look to the CDC for reliable and updated health information about the Coronavirus. The CDC issued interim guidance for employers to assist them in responding to employee questions. The CDC indicates that all employers need to take an active role in reducing the spread of Coronavirus as best they can.

In light of President Trump’s “30 Days to Slow the Spread” guidelines, employers should—at a minimum—encourage employees with symptoms (fever, cough, or shortness of breath) to stay home and contact their medical providers. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commissions (EEOC), the federal agency that protects and enforces employees’ civil rights, stated employers can ask employees about their symptoms, require employees to stay home who are sick, and even take employees’ temperatures.

Employees should not return to work unless they comply with the CDC’s home-isolation guidelines. Sick employees should not be allowed to return to work until 24 hours after they are symptom free. Employers should also comply with social distancing to the extent they can.

Employers may require workers who take time off work during the pandemic to provide a doctor’s note certifying they are safe to return to work.

The EEOC published comprehensive guidelines for employers, which can be found here. Although the EEOC has given employers wider latitude than normal to deal with employees who contract or might contract the virus, employers should not terminate an employee due to a positive Coronavirus diagnosis. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), employers covered under the ADA should not terminate an employee due to a diagnosis or because he or she is displaying symptoms. In Greenway v. Buffalo Hilton Hotel, a New York federal court reiterated that the ADA protects employees from discrimination based on a disability protected under the ADA. In that case, the court held that a hotel wrongfully terminated an employee because of his status as HIV positive. Under the ADA and New York State’s Human Rights Law, HIV is a protected disability, and employers cannot discriminate against an employee based on that disability.

Greenway is instructive because an argument can be made the Coronavirus meets the definition of a disability under the ADA. An ADA disability is any substantial impairment that prevents someone from hearing, speaking, breathing, among other things. Since Coronavirus significantly inhibits the respiratory system, one could argue it qualifies as a disability. Although no case law, regulation, or statute currently supports that argument, employers should err on the side of caution and engage in the interactive process when an employee shares that he or she tested positive for the virus. Employers should determine if accommodations can be made for the employee to work at home or whether it is feasible for the employee to take time off until he or she is symptom free.

Further, if the employer has over 50 employees and must comply with the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA), a sick employee may be entitled to 12 weeks of unpaid leave and job protection. Each state may have its own FMLA that provides additional or more expansive protections to employees. Thus, the employer should be sure provide notice to employees who test positive as per state law and federal ADA and FMLA laws.

Employers should also develop their own plan to respond to Coronavirus concerns. Plans should include how to quickly communicate reliable information with employees, procedures for regular and increased sanitation efforts, and consistent monitoring of state and federal communications regarding Coronavirus.

Closure of Non-Essential Business and Notice to Employees

Many non-essential employers have closed in response to orders issued by state and local government officials, but some non-essential businesses continue to operate. It is unclear whether there will be penalties or criminal action taken against non-essential businesses still operating in violation of state orders.

Employers who have 100 employees or more must provide at least 60 days’ notice before temporary closure under the Worker Adjustment Retraining Notification Act (WARN). The WARN Act requires advance notice when a shutdown will (1) affect more than 50 employees at a single site and (2) will result in a 50 percent reduction in hours for employees during the shutdown. However, notice is not required where the shutdown results from a “natural disaster” or “unforeseeable business circumstances.” Whether the pandemic qualifies as either is currently unclear.

Furthermore, many states adopted their own WARN acts. For example, California Labor Code sections 1400-1408 mirrors the federal WARN Act and requires a 60-day notice by employers prior to a plant closure or mass layoff. New Jersey’s recently revised WARN Act, called the Millville Dallas Airmotive Plant Job Loss Notification Act, requires 90-day notice and forces employers to pay severance for mass layoffs.

Large employers should consult counsel to determine whether the WARN act applies to closures or temporary layoffs in response to Coronavirus.

Treatment of Employees who Raise Safety Concerns

Employers should not take adverse actions against employees who make complaints about potential workplace safety violations related to Coronavirus. There are reports that Amazon terminated a New York employee who led a strike for safer working conditions due to complaints of crowded warehouse floors and multiple employees allegedly already had tested positive Coronavirus. Under 29 C.F.R. section 1977.12(a), OSHA prohibits “discrimination occurring because of the exercise ‘of any right afforded by this Act.’” Thus, employers should consult counsel before taking an adverse action against an employee who raises concerns related to workplace safety and Coronavirus.

Generally, employees are not protected if they refuse to work out of fear of contracting an illness at work unless they are in “imminent danger.” Imminent danger under OSHA means a threat of death or serious physical harm. Employees may rightfully refuse to perform work under OSHA where (1) they request an employer to eliminate a workplace hazard, (2) refuse to work due to a genuine belief of an imminent danger, (3) a reasonable person would also agreed there is a real risk of injury, and (4) there is not sufficient time to address the hazard with OSHA, such as through an inspection.

When an employee refuses to come to work under those circumstances, an employer cannot retaliate against the employee. Here, depending on the type of work and workplace, an employee may be justified in refusing to work if employers do not address workplace conditions that present an imminent danger.

Furthermore, both union and non-union laborers may be protected under the National Labor Relations Act if they are deemed to be engaging in protected activity when raising concerns over workplace safety. An example of this is a group of employees talking about working conditions or participating in a group refusal to work in unsafe conditions, such as in the Amazon strike discussed above.

Communication with Employees

Communication is key in this time of crisis. Employers should establish protocols to consistently communicate with employees. Employers should monitor the CDC’s website and let employees know that they will share information with them as it becomes available. Employers should also keep an eye on state and local government orders to ensure compliance and keep employees abreast of the state of Coronavirus as it develops.